This the first in our series of lessons of influential people who have written about media and its effect on people. One of the things that sticks out when reviewing most all software design models is that you needs analyze your audience. In doing that, you must also pay attention to those things that affect how your audience thinks, learns, and communicates. One of the most influential thinkers on this subject was Marshall McLuhan. The interesting thing about his work is that, by reading his thoughts you would think he was living today. Actually he died much prior to the Internet , PC, and all the pervasive media around us today. Yet, he seemed to sense where we were going as a digital culture. The more you study him the more you should realize this.

McLuhan was born on July 21, 1911 in Edmonton, Alberta. McLuhan professed not to be bothered, at least in retrospect, by his growing up in a backwater—his family moved to Winnipeg, Manitoba, a few years after his birth and McLuhan remained there until he attained an M.A. in English literature from the University of Manitoba in 1934.

After leaving Manitoba, he spent two years acquiring a B.A. from Cambridge University. There he studied under I. A. Richards, a psychologist turned literary critic who examined the process of reading. For Richards it was not the paraphrasable content of a poem that mattered but the way the poem communicated certain effects in the mind of a reader. In later years, McLuhan adapted this technique to the study of media, inspired as well by another Cambridge professor, F. R. Leavis, who urged his students to analyze their cultural environment— advertisements in particular—in the same way they analyzed literature. McLuhan’s first book, The Mechanical Bride, published in 1951, was very much an exercise in cultural criticism in the Leavis mode, a series of essays on advertisements, laying bare their cultural roots and assumptions.

After he left Cambridge in 1936, McLuhan taught for a year at the University of Wisconsin, and then, following his conversion to Catholicism, he joined the faculty of a Jesuit institution, the University of St. Louis. There he married a Texas drama student named Corinne Keller Lewis, with whom he had six children. In 1944 he returned to Canada where he taught for two years at what was then known as Assumption College in Windsor, Ontario, before finally settling at the University of Toronto, his home for the rest of his career. Here he met a political economist named Harold Innis who had discovered that certain media of communication are time based and certain media—more portable and ephemeral—are space based. Working with this hint, and discovering simultaneously in the works of James Joyce, notably Finnegans Wake, a critique of radio and television, McLuhan articulated his perceptions of media as extensions of the human body, and of electronic media, in particular, as extensions of the nervous system, imposing, like poetry, their own assumptions on the psyche of the user.

Some interesting quotes remain in the public domain and remain a part of our everyday thoughts abut the media, including:

With telephone and TV it is not so much the message as the sender that is “sent.” In short, the medium that communicates the message helps define both the message that is received and (which is my point here… ) the those who utilize that medium the most.

My point is, if we are indeed living in a digital world then there are things about these kids that we should be learning about in order to reach them, build media products for them, and so forth. The best place to start is to discover Marshall McLuhan, the father of these ideas.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is the title of the book “The medium is the massage” and not “The medium is the message”? (this is one of the books that McLuhan is most famous for)

Actually, the title was a mistake. When the book came back from the typesetter’s, it had on the cover “Massage” as it still does. The title was supposed to have read “The Medium is the Message” but the typesetter had made an error. When Marshall McLuhan saw the typo he exclaimed, “Leave it alone! It’s great, and right on target!” Now there are possible four readings for the last word of the title, all of them accurate: “Message” and “Mess Age,” “Massage” and “Mass Age.”

On media and technologies as Extensions of Man (subtitle of Understanding Media)

It was R. W. Emerson who wrote that “The human body is the magazine of inventions, the patent-office, where are the models from which every hint was taken. All the tools and engines on earth are only extensions of its limbs and senses” (1870). This is where McLuhan borrowed the idea that media, as an invention of man, is actually an extension of man.. just like one of his limbs.. etc…. etc>)

On the source of the phrase, Global Village

As to the origin of the term “global village” in McLuhan’s work. it has been variously attributed, to Teilhard de Chardin, for example. He did not get it from Teilhard, however. As far as I have been able to ascertain, it comes from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake or else from P. Wyndham Lewis’s America and Cosmic Man—if it comes from anywhere.

Joyce published Finnegans Wake in 1939. In it he uses two phrases, both allude to the Pope’s annual Easter message to the City (of Rome) and the World: Urbi et Orbi. Joyce turned this into “urban and orbal” in one place in the Wake, and into “the urb, it orbs” in another.

The painter and writer, Wyndham Lewis and McLuhan were close friends in the 40s and 50s. Lewis published America and Cosmic Man in 1948 (Britain) and 1949 (US). Here is the eleventh paragraph of Chapter Two of that book:

If you look at North America on the map of the world, you see a very uniform mass. It is more concentrated and uniform than any other land mass. You see an immense area full of people speaking one tongue: not a checkerboard of “united states” at all but one huge State. “United States” is today a misnomer. And since plural sovereignty anyway–now that the earth has become one big village, with telephones laid on from one end to the other, and air transport, both speedy and safe must be a little farcical, the plurality implied in that title could be removed as a good example to the rest of the world, and the U. S. A. become the American Union.

Now, McLuhan was a great fan of Joyce’s and had read the Wake closely for years. Also he and Lewis discussed these and related matters frequently during the years of their association. And he had marked the phrases in Joyce and the paragraph in Lewis’s book, and pointed them both out at one time or another. But I think the truth of the matter simply that he was thinking along those lines and came up with the phrase and after the fact found it echoed in both writers.

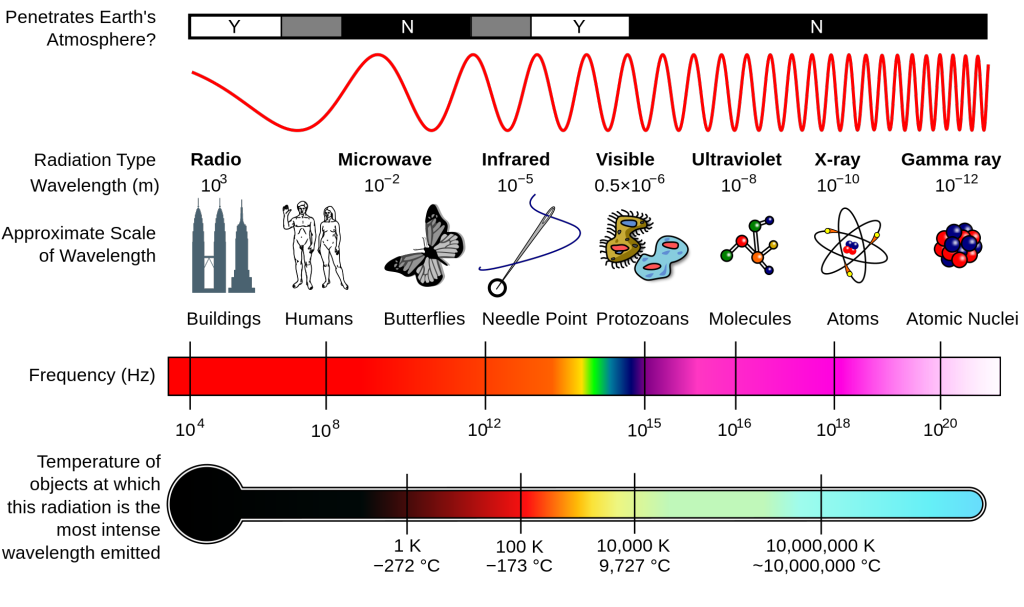

In Understanding Media he put the matter this way: “…since the inception of the telegraph and radio, the globe has contracted, spatially, into a single large village. Tribalism is our only resource since the electro-magnetic discovery. Moving from print to electronic media we have given up an eye for an ear.” (xii-xiii)

On “The Medium is the Message”

Each medium, independent of the content it mediates, has its own intrinsic effects which are its unique message. The message of any medium or technology is the change of scale or pace or pattern that it introduces into human affairs. The railway did not introduce movement or transportation or wheel or road into human society, but it accelerated and enlarged the scale of previous human functions, creating totally new kinds of cities and new kinds of work and leisure. This happened whether the railway functioned in a tropical or northern environment, and is quite independent of the freight or content of the railway medium. (Understanding Media, N. Y., 1964, p. 8)

What McLuhan writes about the railroad applies with equal validity to the media of print, television, computers and now the Internet. “The medium is the message” because it is the “medium that shapes and controls the scale and form of human association and action.” (p. 9)

So where do we go from here?

Let’s take a look at some of his more important works:

The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962)

McLuhan’s The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man is a pioneering study in the fields of oral culture, print culture, cultural studies, and media ecology.

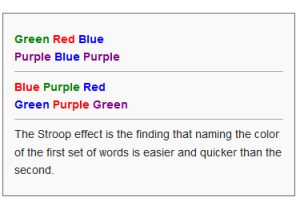

Throughout the book, McLuhan takes pains to reveal how communication technology (alphabetic writing, the printing press, and the electronic media) affects cognitive organization, which in turn has profound ramifications for social organization:

The global village (a term he invented in the 1960s)

In the early 1960s, McLuhan wrote that the visual, individualistic print culture would soon be brought to an end by what he called “electronic interdependence”: when electronic media replace visual culture with aural/oral culture. In this new age, humankind will move from individualism and fragmentation to a collective identity, with a “tribal base.” McLuhan’s coinage for this new social organization is the global village. The term is sometimes described as having negative connotations in The Gutenberg Galaxy, but McLuhan himself was interested in exploring effects, not making value judgments: Instead of tending towards a vast Alexandrian library the world has become a computer, an electronic brain, exactly as an infantile piece of science fiction. And as our senses have gone outside us, Big Brother goes inside. So, unless aware of this dynamic, we shall at once move into a phase of panic terrors, exactly befitting a small world of tribal drums, total interdependence, and superimposed co-existence. […] Terror is the normal state of any oral society, for in it everything affects everything all the time. […] In our long striving to recover for the Western world a unity of sensibility and of thought and feeling we have no more been prepared to accept the tribal consequences of such unity than we were ready for the fragmentation of the human psyche by print culture.

Key to McLuhan’s argument is the idea that technology has no per se moral bent—it is a tool that profoundly shapes an individual’s and, by extension, a society’s self-conception and realization:

Is it not obvious that there are always enough moral problems without also taking a moral stand on technological grounds? […] Print is the extreme phase of alphabet culture that detribalizes or decollectivizes man in the first instance. Print raises the visual features of alphabet to highest intensity of definition. Thus print carries the individuating power of the phonetic alphabet much further than manuscript culture could ever do. Print is the technology of individualism. If men decided to modify this visual technology by an electric technology, individualism would also be modified. To raise a moral complaint about this is like cussing a buzz-saw for lopping off fingers. “But”, someone says, “we didn’t know it would happen.” Yet even witlessness is not a moral issue. It is a problem, but not a moral problem; and it would be nice to clear away some of the moral fogs that surround our technologies. It would be good for morality.

The moral valence of technology’s effects on cognition is, for McLuhan, a matter of perspective. For instance, McLuhan contrasts the considerable alarm and revulsion that the growing quantity of books aroused in the latter seventeenth century with the modern concern for the “end of the book.” If there can be no universal moral sentence passed on technology, McLuhan believes that “there can only be disaster arising from unawareness of the causalities and effects inherent in our technologies.”

Though the World Wide Web was invented thirty years after The Gutenberg Galaxy was published, McLuhan may have coined and certainly popularized the usage of the term “surfing” to refer to rapid, irregular and multi-directional movement through a heterogeneous body of documents or knowledge, e.g., statements like “Heidegger surf-boards along on the electronic wave as triumphantly as Descartes rode the mechanical wave.” Paul Levinson’s 1999 book Digital McLuhan explores the ways that McLuhan’s work can be better understood through the lens of the digital revolution. Later, Bill Stewart’s 2007 “Living Internet” website describes how McLuhan’s “insights made the concept of a global village, interconnected by an electronic nervous system, part of our popular culture well before it actually happened.”

Understanding Media (1964)

McLuhan’s most widely known work, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964), is a pioneering study in media theory. In it McLuhan proposed that media themselves, not the content they carry, should be the focus of study—popularly quoted as “the medium is the message”. McLuhan’s insight was that a medium affects the society in which it plays a role not by the content delivered over the medium, but by the characteristics of the medium itself. McLuhan pointed to the light bulb as a clear demonstration of this concept. A light bulb does not have content in the way that a newspaper has articles or a television has programs, yet it is a medium that has a social effect; that is, a light bulb enables people to create spaces during nighttime that would otherwise be enveloped by darkness. He describes the light bulb as a medium without any content. McLuhan states that “a light bulb creates an environment by its mere presence.” More controversially, he postulated that content had little effect on society—in other words, it did not matter if television broadcasts children’s shows or violent programming, to illustrate one example—the effect of television on society would be identical. He noted that all media have characteristics that engage the viewer in different ways; for instance, a passage in a book could be reread at will, but a movie had to be screened again in its entirety to study any individual part of it.

Tetrad

[one_third]…[/one_third][one_third] [/one_third][one_third_last]…[/one_third_last]

[/one_third][one_third_last]…[/one_third_last]

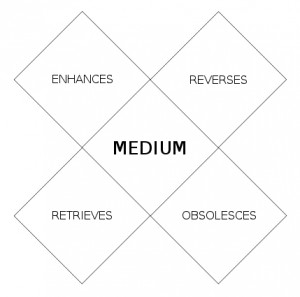

In Laws of Media (1988), published posthumously by his son Eric, McLuhan summarized his ideas about media in a concise tetrad of media effects. The tetrad is a means of examining the effects on society of any technology (i.e., any medium) by dividing its effects into four categories and displaying them simultaneously. McLuhan designed the tetrad as a pedagogical tool, phrasing his laws as questions with which to consider any medium:

- What does the medium enhance?

- What does the medium make obsolete?

- What does the medium retrieve that had been obsolesced earlier?

- What does the medium flip into when pushed to extremes?

The laws of the tetrad exist simultaneously, not successively or chronologically, and allow the questioner to explore the “grammar and syntax” of the “language” of media. McLuhan departs from his mentor Harold Innis in suggesting that a medium “overheats”, or reverses into an opposing form, when taken to its extreme. Visually, a tetrad can be depicted as four diamonds forming an X, with the name of a medium in the center. The two diamonds on the left of a tetrad are the Enhancement and Retrieval qualities of the medium, both Figure qualities. The two diamonds on the right of a tetrad are the Obsolescence and Reversal qualities, both Ground qualities.

Using the example of radio:

- Enhancement (figure): What the medium amplifies or intensifies. Radio amplifies news and music via sound.

- Obsolescence (ground): What the medium drives out of prominence. Radio reduces the importance of print and the visual.

- Retrieval (figure): What the medium recovers which was previously lost. Radio returns the spoken word to the forefront.

- Reversal (ground): What the medium does when pushed to its limits. Acoustic radio flips into audio-visual TV.

Take a look at the above four laws and apply them to ANYTHING you develop or try to sell after the product has been developed… What new does it bring to the table? What does the old knowledge flip into? In other words can the previous untruth mistaken answer become the catalyst for something else? Does that old knowledge misunderstanding ‘reinvent itself” so it too can become new? I have used this diagram to explain almost anything I am trying to introduce.. including story-telling, which I will explain in a later lesson.

[/one_third][one_third_last]

[/one_third][one_third_last]