The goal of this activity is for you to score yourself on the GEFT using the keys provided below and place yourself in one of the grids below based on the results sent to you for the MFFT-20. For the Matching Familiar Figures Test, we scored it because your final result depends on what the others did in your class.

In summary, this activity has two parts:

- Score yourself on the GEFT and review your results from the MFFT-20.

- Then based on the scores and readings, evaluate your scores to decide which of the ecosystems we have discussed this term best applies / would be most useful to you as a student for a given learning situation.

The idea is for you to see how cognitive tempo/style can be a determinant with regards to the best media to use in a class or a course you are asked to design. This exercise correlates to the ‘A’ in the ADDIE model (analyze the learner) in instructional design. I submit that these kinds of tests are more accurate measurements than self-scored instruments because, as we have found out, people do not always learn best from their preferred learning styles. The joke I sometimes use is that I am a visually impaired visual learner. I am only half kidding… sometimes folks have a preferred style but are not very good at using it to learn… we will discuss this in our Synchronous meeting.

Post your reflection about your thoughts on the MFFT-20 and GEFT in the drop box on Canvas.

MFFT-20

The version of the Multiple Familiar Figures Test (MFFT-20) that we are using was originally developed by Cairns and Cammock back in 1984 at the University of Northern Ireland. The sample was middle school students (ages 12-14). This seems to be the most commonly used samples in the previous studies. It is thought that as a person ages, his or her tempo will gravitate towards being more reflective. The instrument Cairns and Cammock used was the original MFFT developed by Jerome Kagan in the 1960s. These instruments were subsequently evaluated for validity and reliability and adapted over time by several individuals (Arizmendi, Paulsen, & Domino, 1981; Block et al., 1974; Watkins, Lee, & Erlich, 1978) to determine whether they actually measured impulsive-reflective tendencies in individuals.

The original format of the MFFT-20 was a paper version in which participants made their choices by selecting the matching figure from a set of six distracters by pointing. The investigator was responsible for manually keeping track of the number of choices made by the participant and utilized an assistant who used a stopwatch to time their latency/delay in making their first response.

For the this automated version I scanned into a computer the paper copies of the figures and alternative choices and imported them into a computer program that was the precursor to Flash (Macromedia Director). The program presents the pictures and their alternatives on a single screen and allows the participant to click on their selection to indicate their response. The computer program automatically keeps track of the total number of choices made before the correct one is selected and the amount of time it takes to make the first pick for each of the item sets.

Recall that you were presented with 20 sample pictures of familiar items and then were asked to identify which one of six alternatives was identical to the sample. If you made an incorrect choice you were subsequently asked by the computer to retry until you made a correct response.

The dividing line between impulsive and reflective quadrants was the median score for latency for this administration of the test (i.e., the average amount of time you delayed until each of you all made your first selections for all 20 pictures) and the median number of errors (also averaged for each participant) The medians were place along horizontal and vertical axes. Based on how each of you fared as compared to the median split lines, you were placed into one of four quadrants made up by the two intersecting axes.

If it was determined that you made relatively quick but inaccurate decisions you were place in the quadrant labeled ‘impulsive’ (Q1). If you were more deliberate (i.e., you showed an increased latency until your first response) and made fewer errors than the calculated median you were determined to be ‘reflective’ (Q2). Those of you who were found to be fast-accurate (i.e., faster and more accurate than the calculated medians) or slow-inaccurate were placed in two other cells (Q3 and Q4 respectively). The ones historically utilized in the administrations of the test are the former(i.e., the impulsive and reflective) quadrants. It is not that the other quadrants do not have matter but comparisons in the research only dealt with the impact of those placed in the first two categories.

| Impulsive: Q-1 |

Slow –Inaccurate: Q-2 |

| Fast-Accurate: Q-3 |

Reflective: Q-4 |

-

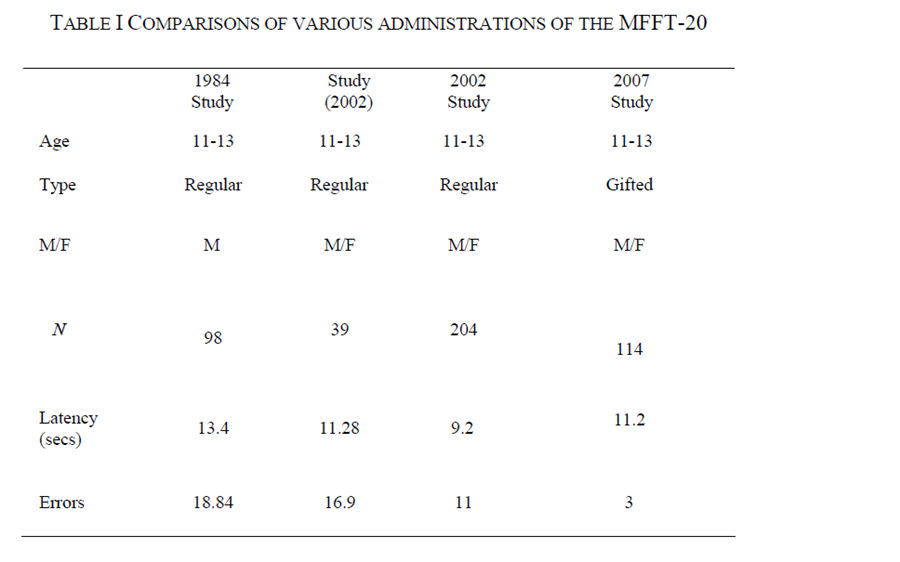

- We will look at our results as well and those from previous administrations of the test during our next Synchronous class Session. In the meantime you will be sent your individual scores via Canvas emails, not that it will mean that much until we meet. Here is a sampling of the scoring that will be presented. The studies from 2002 onward are mine.

- Second, the break points for each quadrant are different for each administration of the test. We will revel those two levels (for speed and accuracy) during our meeting.

According to the literature, (Berry, 1991; Green, 1985) the MFFT (and its various derivations) has been one of the most commonly used and more accurate means to test for cognitive style and to show how individuals perceive and process visual patterns. The MFFT-20 has been found to be the most valid and reliable measurement over time.

But the MFFT has also been the subject to several attempts to refute it as a valid diagnostic test (Salkind & Wright, 1977; Watkins et al., 1978). Ikegulu and Ikegulu (1999) suggested that the notion of a generalized visual processing rate may be questionable, based on the fact that there have been very few repeated measurement studies to test the generalizability of the dimension. That is why I have been looking at this data over the past 16 years. My research further explains what has happened to individuals to coincide with the digital age.

Some research indicates that the ‘impulsive-reflective’ designation might be better depicted on a continuous plane (i.e., from low to high), rather than a bi-polar scale (Salkind & Wright). On the other hand, Salkind and Wright when on to state that in subsequent studies they found continuous scaling to appear to contradict the basic premise of a cognitive style (that is , by its very nature, is bi-polar).

This apparent anomaly appears to some to create a potential lack of power for the impulsive-reflective scale to be useful in the first place. Ault, Mitchell, and Hartmann, (1967) contributed a loss of power to Kagan’s over-reliance on latency rather than number of errors to determine reflective versus impulsivity. The findings of Ault et al seem to contradict Kagan’s original hypothesis… categorizing individuals must be based on the interaction between speed AND error-rate (Kagan, 1965).

In spite of these and other attempts to dispute it, Kagan’s MFFT instrument has generally been overwhelmingly supported in the literature . Many subsequent studies definitively reinforced its validity (Arizmendi et al., 1981; Green, May, 1985).

Cairns and Cammock (1984) developed what has come to be known as the most valid and reliable version of the MFFT (the one that we used). They presented five case studies that asserted an increased reliability and accuracy in that subjects were more accurately categorized into one of the four quadrants (impulsive, reflective, fast-accurate, or slow-inaccurate). Their instrument uses 20 sets of pictures (instead of the 12 in Kagan’s original test) that were reduced down from an original list of 32 items that was, in turn, concatenated and prioritized in several reliability studies. The researchers performed four separate reliability tests of over 300 total additional subjects to develop sets of norms, and established strong correlations between order position (i.e., the order in which the picture sets are presented), error rates, and interactions between age and sex.

One of the most interesting things that I have learned from doing these studies over is that over time (looking back at Cairns and Cammock’s results as compared to the many times I have administered this test) the amount of time it is taking subjects to make their first choice and the number of errors made is shrinking significantly. Remember, the groups are only compared to themselves (i.e., the median scores are self contained within each administration). When looking at this over time, it appears that maybe McLuhan was more right than even he realized… that the medium a person uses not only alters the message but also the person based on one’s tendencies to (over)use that medium.

To me, that is the real story here. The results of the cognitive style measurements I have personally made over time seem to indicate that something about learning styles has changed significantly since the original instrument was analyzed and developed. When you compare the results of MFFT-20 cognitive style in subsequent studies to the norms provided by Cairns and Cammock (1984), not only has the median total number of errors decreased (from 28-30) in the Cairns and Commock studies to eight in an administration I did about 20 years later). Also so did the median latency to first response (from 18 in 1984 to 9.12). These reductions seem to indicate that latencies to first response for visual activities were growing significantly shorter, but the quicker responses do not always translate to higher error rates. The testing I have done indicates that participants appear to be developing a propensity for more correctly remembering things from rapid visual presentations. The results in this class are quite small but they tend to agree with my hypothesis. A modifying factor is age of participants. In most of the studies I have conducted, the participants were generally within one or two years of those in the original study. As you should see, because you folks are a bit older than middle schoolers! It was expected that your scores would be different. But note even with this caveat, your scores were still different than those from 1984.

Another change that is taking place is the shrinking of the differences in visual cognition between males and females. With Cairns and Cammock, female responses were considered to be ‘outliers’ and were systematically eliminated from their study. In subsequent studies that I have done, any differences between males and females that exist have not been significant. While females still may be found to be more reflective than their male counter-parts, these differences seem to be growing smaller.

All of this has tremendous value to our research and decisions about media choices. If our definition about ecosystems holds true, then we can make some interesting observations about our being able to measure psychological responses to the media. I offer you an interesting follow up study to help you look at the implications a bit further.

Download link: http://emeclasses.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/327set4b_learningstyles.pdf“

Group Embedded Figures Test (GEFT)

As you can see, a number of instruments have been developed to measure a person’s cognitive style. One of the easiest to administer, especially in group situations, is the Group Embedded Figures Test (GEFT) The GEFT is a perceptual test that requires the subject to locate a sample figure within a larger complex figure. The GEFT can be administered in about 20 minutes (ours was not timed) and can be quickly scored using answer templates.

The Group Embedded Figures Test (GEFT) was designed by Witkin in 1971 to assess his concept of “field dependence – independence” (e.g., Witkin & Goodenough, 1981). ‘Good performance’ was taken as a marker of field independence… the ability to dis-embed information from context or complex surrounding field. This test requires you to spot a simple form within a more complex figure; the color and form of the latter create a gestalt within which the part is hidden. (Some administrations of the test use color also to distract the participant.

Witkin (1916–1979) was a founder of the notion of determining cognitive and learning styles. He proposed the idea that personality could be measured in part by how people perceived their environment. In particular, he attempted to create objective tests (in contrast to questionnaire methods), such as the Rod-and-Frame test, to measure individual differences in reliance on external versus internal frames of reference. The Embedded Figures Test was created by Witkin as a more portable and convenient test designed to measure these same facets of field dependence or independence.

Witkin spent much of his academic career developing measures of learning style. His research showed that there were differences in how people perceived discrete items within a surrounding field. People at the one end of the extreme where perception was strongly dominated by the prevailing field are designated “field-dependent.” Field-dependent learners see the forest. At the other extreme, people are considered “field-independent”, if they experience items as more or less separate from the field. Whereas field-dependent people see the forest, field-independent learners see the tree within the forest. Since scores on learning style tests form a continuous scale, the terms field-dependent and field-independent reflect a tendency, in varying degrees of strength, toward one end of the extreme (field-dependent) or the other (field-independent) (Witkin et al, 1977).

On all embedded figures tests, the higher the score, the more field-independent the subject, and the lower the score the more field-dependent the subject is. It must be stressed that learning styles are independent of intelligence (i.e., does not measure IQ). Remember, field-dependence/field-independence is more related to the PROCESS of learning, not the APTITUDE for learning. Both field-dependent and field-independent people make equally good students as well as teachers.

The embedded figures test is another measurement we can use to detect intellectual development. Because longitudinal studies do not appear in the literature we can easily detect trends. I have been keeping anecdotal records of results over time and am beginning to see trends. I also believe at this time the scoring norms most likely needs to be adjusted and is a project I have on the back burner.

References

Arizmendi, T., Paulsen, K., & Domino, G. (1981, Spring). The Matching Familiar Figures Test: A primary, secondary, and tertiary evaluation. Journal of Psychology, 812-818.

Ault, R. L., Mitchell, C., & Hartmann, D. P. (1967). Some methodological problems in reflective-impulsivity. Child Development, 47, 227-231.

Berry, L. H. (1991). Visual complexity and pictorial memory: A fifteen-year research perspective. Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the Association for Educational Communications and Technology. (ERIC Documentation Reproduction Service No. 334 975).

Block, J., Block, J. H., & Harrington, D. M. (1974). Some misgivings about the Matching Familiar Figures Test as a measure of reflection-impulsivity. Journal of Developmental Psychology, 10, 611-632.

Cairns, J., & Cammock, T. (1984). The 20-Item Matching Familiar Figures Test. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service: No. 015681-4).

Green, K. E. (1985). Cognitive style: A review of the literature . Chicago, IL: Johnson O’Connor Research Foundation, Human Engineering Lab. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 289 902).

Salkind, N. J., & Wright, J. C. (1977). The development of reflection-impulsivity and cognitive efficiency. Human Development, 20, 377-387.

Watkins, J. M., Lee, H. B., & Erlich, O. (1978). The generalizability of the matching familiar figures test. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 175 882), Toronto, CA.

Witkin, H. A., & Goodenough, D. R. (1981). Cognitive styles: Essence and origins. Field dependence and field independence. New York: International Universities Press.