Below are a few theorists’ view on how learning actually takes place through (the inherent need to) change:

Driscoll

Driscoll (2000) defines learning as “a persisting change in human performance or performance potential…[which] must come about as a result of the learner’s experience and interaction with the world” (p.11).

Notice the link between learning and change. That is why you may hear me on my soapbox about how narrative structure (that includes the concept of transformation/change in the main character, cause and effect, and judgments) makes for a good construct upon which you can build an effective learning strategy.

Driscoll’s definition encompasses many of the attributes commonly associated with behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism – namely, learning as a lasting changed state (emotional, mental, physiological (i.e. skills)) brought about as a result of experiences and interactions with content or other people.

Lewin

Kurt Lewin is another person who espoused the concept of linking learning with a change in state. Given the relationship of Diffusion Theory as applied to social systems, Lewin’s principles of social psychology relate very well. Lewin’s basic change model of unfreezing, changing, and refreezing may be a solid theoretical foundation upon which change theory can be built. The key, of course, is to see that human change, whether at the individual or group level, is a profound psychological dynamic process that involves painful unlearning without loss of ego identity and difficult relearning as one cognitively attempted to restructure one’s thoughts, perceptions, feelings, and attitudes.

[Sidebar: Note the correlation between change theory and motivation theories we discussed previously

Unfreezing is a concept that entered the change literature very early on and highlighted an observation that the[ stability of human behavior was based on “quasi- stationary equilibria” supported by a large force field of driving and restraining forces.

For change to occur, this force field has to be altered under complex psychological conditions because, as is often noted, just adding a driving force toward change often produces an immediate counter-force to maintain the equilibrium. (Thus, the explanation of Piaget’s disequilibrium, as well as the ‘disruption’ to harmony as explained by those who espouse narrative epistemology. This observation led to the important insight that the equilibrium could more easily be moved if one could remove restraining forces since there were usually already driving forces in the system.

Unfortunately, restraining forces are harder to get at because they are often personal psychological defenses or group norms embedded in the organizational or community culture.

All forms of learning and change start with some form of dissatisfaction or frustration generated by data that disconfirm our expectations or hopes. Whether we are talking about adaptation to some new environmental circumstances that thwart the satisfaction of some need, or whether we are talking about genuinely creative and generative learning of the kind Peter Senge focuses on, some disequilibrium based on disconfirming information is a prerequisite (Senge, 1990). Disconfirmation, whatever its source, functions as a primary driving force in the quasi-stationary equilibrium.

Disconfirming information is not enough, however, because we can ignore the information, dismiss it as irrelevant, blame the undesired outcome on others or fate, or, as is most common, simply deny its validity. In order to become motivated to change, we must accept the information and connect it to something we care about. The disconfirmation must arouse what we can call survival anxiety” or the feeling that if we do not change we will fail to meet our needs or fail to achieve some goals or ideals that we have set for ourselves (i.e., “survival guilt”).

In order to feel survival anxiety or guilt, we must accept the disconfirming data as valid and relevant (ARCS?). What typically prevents us from doing so, what causes us to react defensively, is a second kind of anxiety which we can call “learning anxiety,” or the feeling that if we allow ourselves to enter a learning or change process, if we admit to ourselves and others that something is wrong or imperfect, we will lose our effectiveness, our self-esteem and maybe even our identity (remove the fear of being wrong). Most humans need to assume that they are doing their best at all times, and it may be a real loss of face to accept and even “embrace” errors (Michael, 1973, 1993). Adapting poorly or failing to meet our creative potential often looks more desirable than risking failure and loss of self-esteem in the learning process.

Learning anxiety is the fundamental restraining force which can go up in direct proportion to the amount of disconfirmation, leading to the maintenance of the equilibrium by defensive avoidance of the disconfirming information. It is the dealing with learning anxiety, then, that is the key to producing change, and Lewin understood this better than anyone. His involving of workers on the pajama assembly line, his helping the housewives groups to identify their fear of being seen as less “good” in the community if they used the new proposed meats and his helping them to evolve new norms, was a direct attempt to deal with learning anxiety. This process can be conceptualized in its own right as creating for the learner some degree of “psychological safety.”

Mezirow

His “Transformative Dimensions of Learning, explored some of the processes by which people can free themselves from ‘oppressive ideologies, habits of perception, and psychological distractions’. He spent considerable time drawing on psycho-analytical, behavioristic and humanistic theories.

Freire

Paolo Freire’s work: “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” is a classic account of his position that learning erupts from one’s dissatisfaction with their current state. He also followed this up with another tome on Learning to Question. A pedagogy of liberation in which he gives an account of learning through problem-posing. His work is strongly connected with the ideas about informal learning.

Correlation of Change Theory to Motivation

This should be rather obvious. All of these conceptualizers confirm the idea that, unless sufficient psychological safety is created, the disconfirming information will be denied or in other ways defended against,

no survival anxiety will be felt, and, consequently, no change will take place. The key to effective change management, then, becomes the ability to balance the amount of threat produced by disconfirming data with enough psychological safety to allow the change target to accept the information, feel the survival anxiety, and become motivated to change.

By what means does a motivated learner learn something new when we are dealing with thought processes, feelings, values, and attitudes? Fundamentally it is a process of “cognitive restructuring,” which has been labeled by many others as frame braking or re-framing.

It occurs by taking in new information that has one or more of the following impacts:

- semantic redefinition–we learn that words can mean something different from what we had assumed;

- cognitive broadening–we learn that a given concept can be much more broadly interpreted than what we had assumed; and

- new standards of judgment or evaluation

The new information that makes any or all of these processes possible comes into us by one of two fundamental mechanisms:

- learning through positive or defensive identification with some available positive or negative role model, or

- learning through a trial and error process based on scanning the environment for new concepts (Schein, 1968).(Is this “Social Learning” and “learning through pattern recognition“?)

A learner or change target can be highly motivated to learn something, yet have no role models nor initial feeling for where the answer or solution might lie. The learner then searches or scans by reading, traveling, talking to people, hiring consultants, entering therapy, going back to school, etc. to expose him or herself to a variety of new information that might reveal a solution to the problem. Alternatively, when the learner finally feels psychologically safe, he or she may experience spontaneously an insight that spells out the solution. Change agents such as process consultants or non-directive therapists count on such insights because of the assumption that the best and most stable solution will be one that the learner has invented for him or herself.

Once some cognitive redefinition has taken place, the new mental categories are tested with new behavior which leads to a period of trial and error and either reinforces the new categories or starts a new cycle of disconfirmation and search.

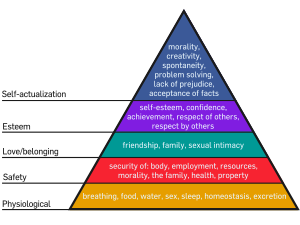

Maslow discussed all of this in his book: “Towards a Psychology of Being”. He argued for the significance of self-actualization. His theory of motivation moves from low to high level needs (physiological, safety, love and’ belongingness’, self-esteem, self-actualization).

Disequilibriation (see Piaget) and disambiguation as they relate to System/Social Change

Having a ‘theory in use’ is not good enough, by itself. The people involved must also be pushed to go on the next level, to make their theory of action explicit

On a larger scale… and considering things like Action research… one must wonder, if theories of action do not include the harder questions – ‘Under what conditions will continuous improvement happen?’ and, correspondingly, ‘How do we change cultures?’ … if we do not investigate this level, then all theories of change are bound to fail.

So, we have a ‘standards-based’ system-wide reform that sounds like it should work. The potential for failure is that the strategy lacks a focus on standards, rather than one that delves into questioning what needs to change in instructional practice and, equally important, what it will take to bring about these changes in classrooms across the districts.

In short, the major change needed is a change in the culture… to create a ‘culture of learning’

Here’s another concept to tackle: social entrepreneurship. Ok, so, again, I borrow form Wikipedia, but it does do a pretty good job summarizing it all up:

“Social entrepreneurship is the work of social entrepreneurs. A social entrepreneur recognizes a social problem and uses entrepreneurial principles to organize, create and manage a venture to achieve social change (a social venture). While a business entrepreneur typically measures performance in profit and return, a social entrepreneur focuses on creating social capital. Thus, the main aim of social entrepreneurship is to further social and environmental goals. Social entrepreneurs are most commonly associated with the voluntary and not-for-profit sectors,[1] but this need not preclude making a profit. Social entrepreneurship practiced with a world view or international context is called international social entrepreneurship”.

The terms social entrepreneur and social entrepreneurship was first promoted in the 1970s and later in the 1980s and 90s by Bill Drayton the founder of Ashoka and others such as Charles Leadbeater. From the 1950s to the 1990s, Michael Young was a leading promoter of social enterprise because of his role in creating more than sixty new organizations worldwide, including a series of Schools for Social Entrepreneurs in the UK. Another British social entrepreneur is Lord Mawson who created the renowned Bromley by Bow Centre in East London. He recorded these experiences in his book “The Social Entrepreneur: Making Communities Work“. The National Center for Social Entrepreneurs was founded in 1985 by Judson Bemis and Robert M. Price.

Although the terms are relatively new, social entrepreneurs and social entrepreneurship can be found throughout history. A list of a few historically noteworthy people whose work exemplifies classic “social entrepreneurship” might include Florence Nightingale (founder of the first nursing school and developer of modern nursing practices), Robert Owen (founder of the cooperative movement), and Vinoba Bhave (founder of India’s Land Gift Movement). During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries some of the most successful social entrepreneurs successfully straddled the civic, governmental, and business worlds – promoting ideas that were taken up by mainstream public services in welfare, schools, and health care.

The concept of social entrepreneurship is simple (although not the easiest to implement): create opportunity zones to empower impoverished individuals by teaching them how to ‘monetize’ their knowledge. Locally, we have been working with AFCAAM in the Dunbar area through our Digital YoUth camps where we teach students how to produce media for purposes of creating a business entity in which these students will be marketing their services to the local community. The idea is to create a revenue stream and build resumes in order for them to find employment (or create businesses) .. kind of like a ‘self-help’ stimulus plan.

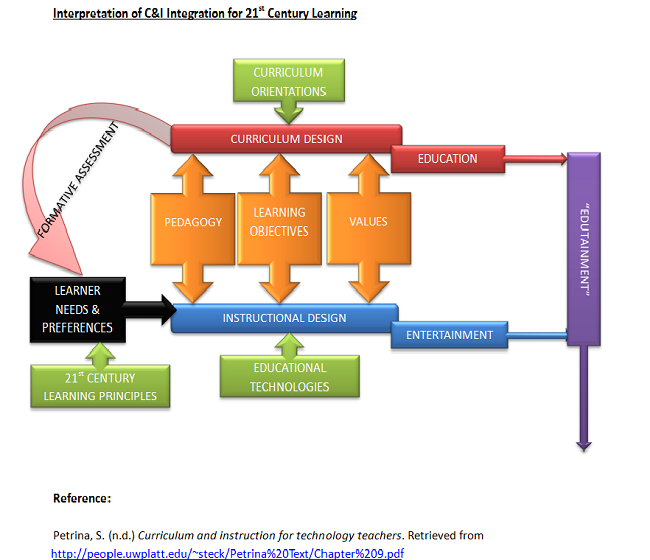

Now, I know this is a lot more of a reach than what you might have first thought when looking at this topic in an Instructional Design course.. but it follows that if teaching and learning is all about change, your instructional plan must include a ‘mission’ statement that includes thoughts on what is it that you are attempting to change in your students? is it attitudes?, knowledge that is to be acquired? psycho-motor training? or a much larger change.. social change!.. these are important considerations when designing any instruction.

Key ‘Takeaways’:

- Learning is very similar to change/diffusion in that what we are attempting to do is get students to change behavior and/or change their way of thinking about things. There are many parallels between organizational change management and learning management.

- If the best way to initiate change in an organization is to get individuals involved in a real project, then it follows that to get students to accept the changes you are presenting them with is to do the same thing… change attitudes/behaviors and motivate through authentic learning activities.

- One of the most powerful sources of motivation to work through all the frustrations involved in managing change is to require regular progress reports “teammates” and faculty. Implementing peer evaluation of these projects is a powerful motivator… even more so than grades sometimes.

- A motivator won’t go anywhere unless other conditions inspire one to mobilize (a la Mezirow, Piaget, and Freire).

These ‘conditions’ include:

- a common moral purpose/mission

- the capacity to change

- applying the proper resources, and

- peer and leadership support

It is the combination of the above elements that makes the motivational difference.

This can even relate to non-classroom situations, such as school counseling, Safe Coordinators, etc. who are helping youths ‘change’ their outlook by helping them to focus on doing the right thing… making good choices, etc.. what is known in K-12 settings as dispositions.

Kenny/Wirth Article on Effective Teaching

This article highlights some application of these concepts.. The article presents ideas on the kinds of practices one can introduce in instruction that elicit changes in the students you are attempting to reach.

[pdf http://rkenny.org/6284/Kenny.pdf 800 600]

Here is a link to the actual publication at the journal.

Do This!

Let’s do something interesting:

This topic involves a whole lot more than you might have thought about when beginning… and the idea of using the classroom to foster social change may sound a bit political.. but be assured that is not the intent here.. especially for those whose interests involve business and industry training and not the K-12 classroom.

Perhaps the best way for you to take away something valuable is to design a short module in which you highlight the change process:

- In a few short sentences, describe the course/class/module/unit in terms of the kind(s) of change you are interested in bringing about in your students…

- Describe your learners (age; PreK-12?; Business/Industry?) Anything you can tell me as a reviewer that will help place the lesson in context.

- How you would go about motivating the learners in terms of the desired change(s)? Is it attitudinal (dispositions), psycho-motor? cognitive? How would you measure your success in this regard?

HINT: Look specifically in the motivational concepts listed under “What you should take from this” section. Describe your efforts to motivate your learners according to these basic questions… while these were written in terms of social change, they apply to the basics of all training/lesson designs.

- Post your ideas and concepts in the Drop Box set up on Canvas.